After College Graduation, Where do Chinese International Students go?

Chinese international students who study in the U.S. find difficulties both in finding jobs and assimilating into new work cultures after they obtain one. Some choose to give themselves a break and seek alternative solutions, while others choose to push themselves to overcome challenges. But for either road, there is no right or wrong answer.

The recent daily routine of Shiyu Pan, a just-graduated journalism student, is presented as the following.

Waking up naturally without the stressful reminders of the alarm, she spends her morning completing an unpaid internship for China Daily, a Chinese bilingual newspaper. She is responsible for translating documents, video editing, and collecting international news stories to bring to her supervisor. After the job is done, she makes herself a simple meal and takes an afternoon nap. Then the time is dedicated to reading, learning extra skills, and volunteering for a public service organization that supports Asian women, in which she interviews injured women, writes articles, and does outreach activities. Around 5:00 pm, she takes her dog for a walk. Her day ends with eating dinner, doing exercises, and watching movies.

This seems to be a perfect balance of a person's life, with things to do and time to relax. But Pan came to this relatively certain point after experiencing a large amount of anxieties in the past few months, which has something to do with the unique circumstances that international students face after college graduation.

Pan was watching the sunset with her friend in Madison before she flew back to China.

Pan was watching the sunset with her friend in Madison before she flew back to China.

After international students graduate from the college, they have two major directions overall. For some who want to stay in the U.S. to find jobs, they have to apply for Optional Practical Training (OPT), a type of visa that allows them to work in areas that are directly related to their majors at least one year after receiving their degrees. After one-year’s permission, they have to deal with other work visas like H1B, which guarantees six years of work permission, but the decision is made through lottery. Other international students might choose or be forced to go back to their countries to work or consider other choices, such as pursuing further studies.

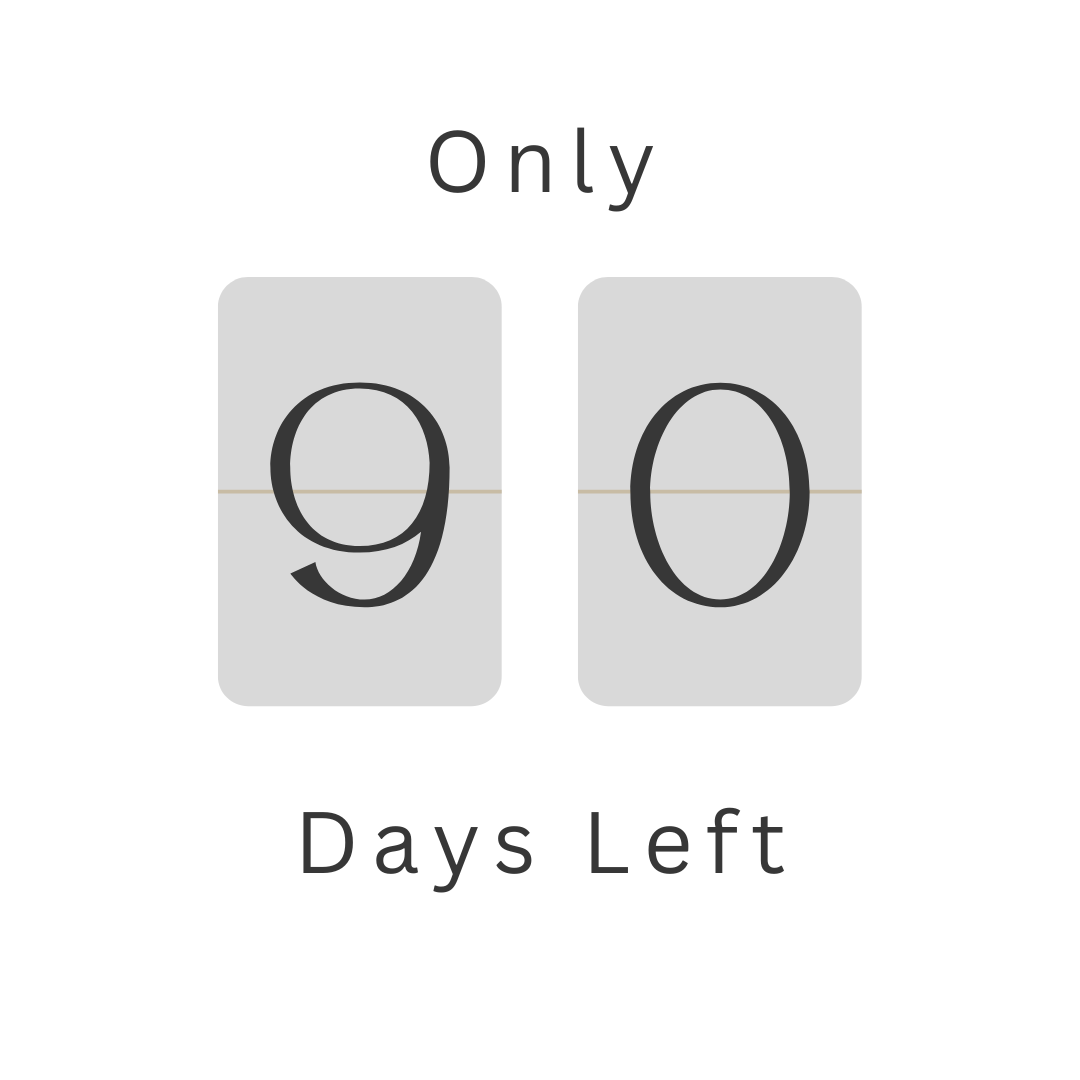

For OPT’s application process, applicants are not required to find a job first. Yet, after their application has been approved, they are in a 90-day countdown: if they don't secure a job or an internship or even start their own business in ninety days, they are unable to stay in the U.S. legally. That is the first obstacle that some international students may face.

Photo made by Luda Tang.

Photo made by Luda Tang.

The journey for Pan to apply for jobs for OPT was not easy after she graduated from college in May 2022. She encountered round after round of rejections. The resumes and cover letters that she had worked on and sent out sank into the sea without a trace.

Pan said, “The journalism-related jobs I applied for had almost no responses at all. Only a few unpaid positions later responded to me and offered interviews.”

“There's definitely students that get fantastic jobs, and they have wonderful placements. But we do also have students that apply [for] dozens of jobs and don't get an interview. Or sometimes we'll have students that are offered a job, and then it's rescinded because the potential employers realize that they only have one year of work permission,” said Andrea Popa, the director of International Students Affair offices of Emerson College.

The limited one-year permission is one handicap. It puts international students in a spot that when employees have two comparable candidates for the same job, they prefer to choose the applicant with citizenship because companies don't have to invest money and time into sponsorship for work visas.

However, the one-year work permission isn’t the only disadvantage that international students have. For international students who are majoring in liberal arts, which requires higher ability on verbal comprehension and writing, they experience increased hardship in receiving responses.

“It’s actually not that OPT makes jobs hard to find, but it’s our major that makes it hard to compete with a native speaker,” Pan said.

According to the statistics from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York about recent graduates’ labor market in 2021, the unemployment rate of college graduates who are majoring in mass media reached 7.3%, while traditional subjects like sociology, fine arts, anthropology ranged from 5% to 6 %. Subjects with the lowest unemployment rates were medicine, technology and education from 1% to less than 3%, including majors like early childhood education, medical technicians, and civil engineering.

These numbers show difficulties of being employed for domestic college graduate with liberal arts majors. Then, for international students who have the same focus, their obstacles will only be amplified.

But one thing to notice is that not all OPT allows only one-year work permission. Students who are majoring in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) fields are allowed to extend their OPT for another 24 months. The permission of a longer time gives candidates a higher chance of being employed. According to the data from the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in 2018 about the companies that hire OPT participants at relatively higher rates, the top seven OPT employers include Amazon, Integra Technologies LLC, Intel Corporation, Google, Microsoft Corporation, Facebook and Tellon Trading, Inc, which are all technology companies.

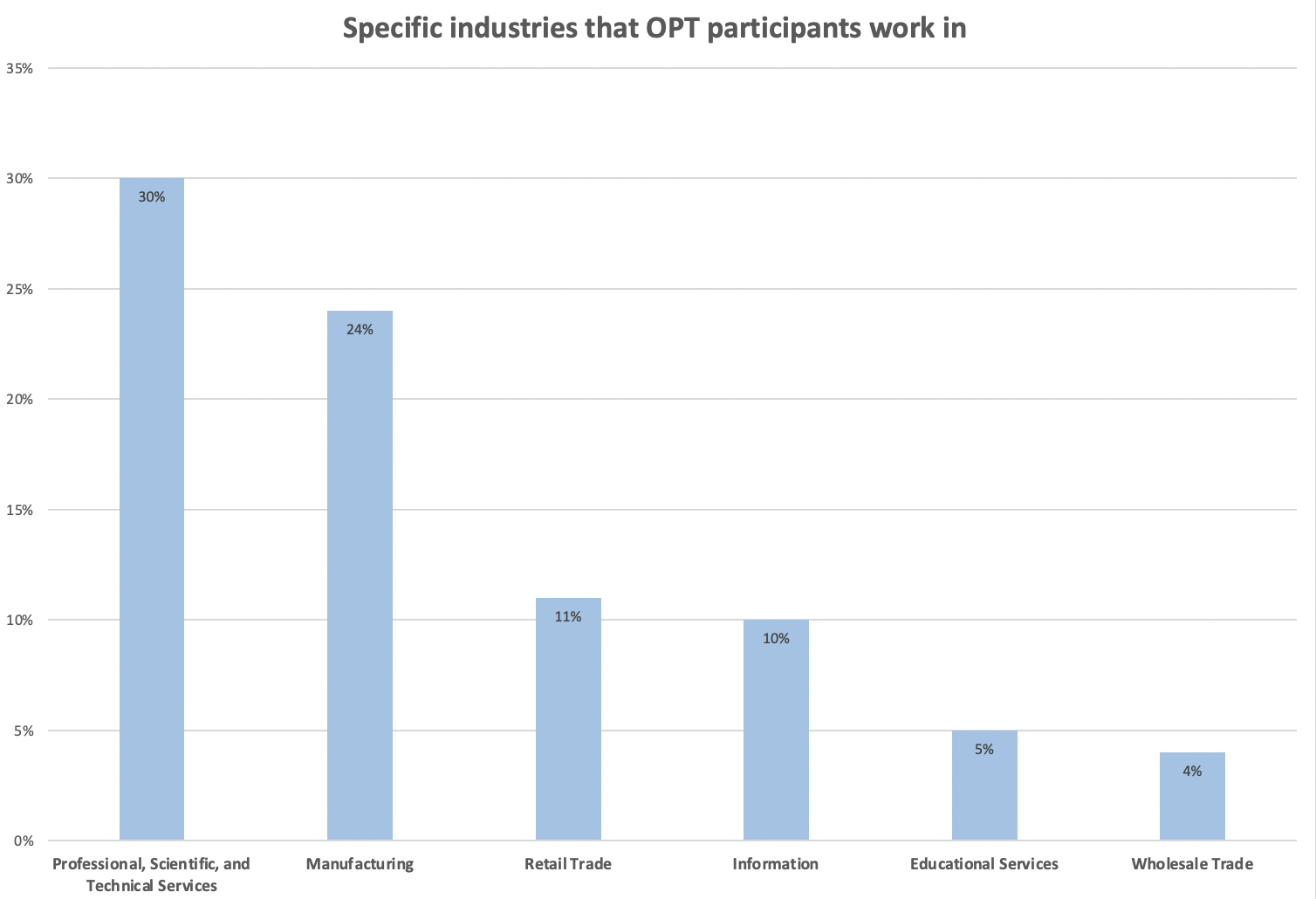

This result can also be supplemented by a report from the Department of Labor in 2019, which shows the specific industries that OPT participants work in.

The report shows that 30% of students who participated in OPT are working in industries like professional, scientific and technical services. This number was followed by 24% of OPT participants working in manufacturing, 11% in retail trade and 10% in information. These statistics all reflect the fact that international students who are liberal arts majors, compared with students with STEM majors, face a bigger challenge in finding employment.

“Most of my peers who are STEM majors have gotten jobs. They probably started to submit resumes at the beginning of their senior year, then went through several rounds of interviews, and finally got the offer before graduation,” Pan said.

“I think, jobs like marketing, communication, and communication sciences disorders, those more clinical or practical sort of jobs, maybe are more likely for people to find a job. I think our students that are in subjects like film, that it's okay to find projects, but it's more difficult to find a job,” said Popa.

Besides the practical pains of securing a job, the sense of unwelcomeness or the inability to fit in also stay with international students along the way.

Nature did a survey about masters’ and PhD students’ experiences and opinions in October this year. It uses a sample of more than 3,250 respondents, including more than 29% of international students. According to the survey, 26% of international students indicated that they have experienced discrimination or harassment during their college studies, while some respondents also show that the same experiences happened to them outside of the university.

Xiangkun Cao, who started a postdoctoral position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology this year and also one respondent of the survey, says in the article that even for students who had already earned master’s or undergraduate degrees at universities in the U.S., they may still face exaggerated criticism of their accent and grammar. The language problem is one of the most mentioned barriers for international students, either in school or in the workplace.

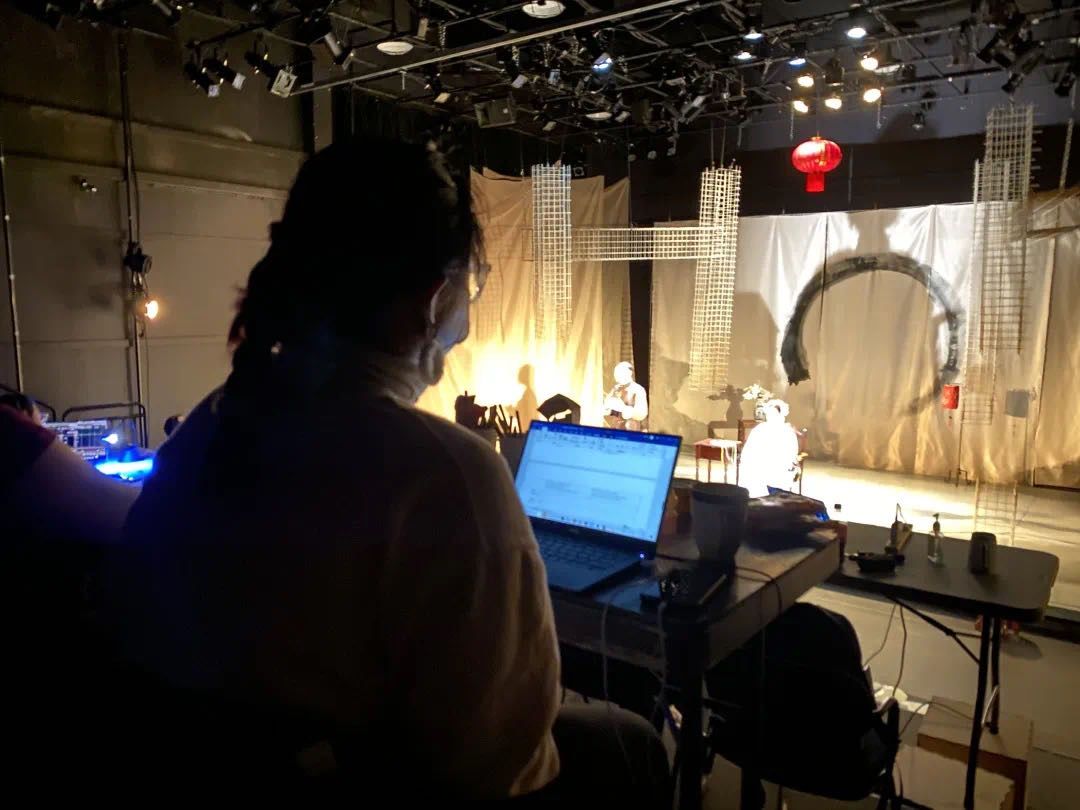

Jingwen Zhang is a theater-major student who just graduated from Emerson College. She successfully got freelance jobs as a stage manager in several theater production crews through referrals of friends. Luckily, Zhang had met supportive and kind colleagues so far. However, she still perceives the language as a big barrier for her to fully assimilate into the group, especially as she considers crew as a working environment that highly requires efficiency and communication skills.

Photo from Zhang. She was an assistant director in the production team of The Chinese Lady.

Photo from Zhang. She was an assistant director in the production team of The Chinese Lady.

In July this year, she participated in the Commonwealth Shakespeare Company’s production of William Shakespeare’s classic comedy “Much Ado About Nothing,” which would be held in Boston Common as an annual event that opens to the public. She perceived this experience as a training camp, making her exhausted both physically— since she had to work outdoors during the hottest days in Boston—and mentally.

“In the first few days, I didn't say a word when I was backstage. I couldn't take their [my colleagues'] jokes at all, and I also didn't know what to say. The only way I can communicate is to ask them questions, like what should we do now,” Zhang said.

If her teammates asked her to get something for them, this was another moment that stressed her out. “Sometimes, they may ask me to find a 2*4 wooden board or a drill in one millimeter. Oh God! I have never seen or used these items in my life,” Zhang said. “I can’t understand what they need to fulfill my job.”

A photo collection made by Zhang, which records her time in the production of "Much Ado About Nothing."

A photo collection made by Zhang, which records her time in the production of "Much Ado About Nothing."

In the first week of her experience, the language barrier and heavy workload caused her a lot of pressure. She talked about how she cried every evening when she was off work, and how she started to think about quitting the job after the first day on set. But now, she says she really appreciated the experience, which offered her insights on how to better communicate with team members and adjust herself to the professional environment.

Nevertheless, even with the huge difficulties of either finding a job or working as an international graduate, applying for OPT seems still to be increasingly popular. Though, the number of applications dropped in recent two years, which might be influenced by the pandemic. From the data collected by Open Doors, an institution that tracks international students’ mobility to the United States, the number of OPT applications has increased from 32,999 in 2004 to 223,539 in 2019. When the U.S. government allowed a two-years extension of STEM OPT in 2016, it led to the largest increase of OPT participation.

But for some students who aren’t majoring in STEM-related fields and have unique needs, finding a job in the U.S. seems to be something they have to do.

Usually, while receiving a college education in the U.S., students tend to find jobs in the market they have their degree in. First, it can add to their competitiveness in the workplace by having diverse work experiences. Second, even though most of the subjects are universal, like economics, computer science, marketing, there are other subjects that work differently in various societies. These subjects could include law, social work and nonprofit management. For this group of students, to successfully apply what they have learned in school to the real world, obtaining a job in the U.S. after graduation seems to be the only way. Kerin Tsui, a junior in Emerson College, falls into this category.

Tsui’s ultimate career goal is to become an on-air news anchor. From her education in the U.S., she was informed that diligence and being comfortable in front of the camera are two primary conditions of achieving her dream. But in China, where Tsui comes from, being a news anchor requires a systematic training on voices, bearing, and sounds, and a rigorous selection process. For someone who hasn’t had such training, Tsui will not be favored if she chooses to go back to China. Yet, that’s not the only reason that Tsui thought she had to find a job in the U.S.

“All the on-air talents back in China sound very much the same. And I am not saying that's necessarily a bad thing. But I am very attracted to how the on-air talents here in the U.S. have their own styles of reporting,” Tsui said.

Click to see Tsui's video as a news anchor in Emerson College's TV station WEBN.

For Tsui, even though she still has one more year of college life, considering how difficult it is to find an appropriate internship now as a student, she can't imagine how bad the situation will be when there is a time limit of one year.

Pan recalled the previous few months were filled with anxieties before she gave up on OPT. The pressure of the high life expenses in the U.S. burdens her with an unpaid job, while simultaneously most of her friends have already chosen to go to graduate school with a definitive goal. Being left alone with an undecided future brings her, or other young graduates who have the same case, with uncertainty and exclusion. Even though she feels she has a more peaceful life now, she might still encounter other forms of pressure. “Taking a gap year also seems to be against our people’s mindset that every period of life should be defined with a title, like being a student or having a job,” Pan said. She not only feels the pressure by being compared with other peers by her parents, but also is often asked by other relatives’ gossipy inquiries: “What are you doing right now?” or “Why don't you have a job?”

Photo by Pan. She went for a walk in a park with her parents on a weekend morning.

Photo by Pan. She went for a walk in a park with her parents on a weekend morning.

Pan thought it’s important to believe in ourselves no matter what has happened.

“You have to know that a gap year is not something you should be ashamed of. It's just a choice, and you're just a year behind others; it doesn't mean anything,” Pan said.